Social Work's Edith Harris lecturer describes benefits of trauma-informed systems

The child welfare system has helped reduce the impact of traumatic events on children with its adoption of "trauma-informed systems" that coordinate the response of caregivers, service providers and community members while employing settings and procedures that reduce trauma triggers, a national child welfare expert told an audience at Wayne State's Community Arts Auditorium on Nov. 10.

Charles Wilson, senior director of the Chadwick Center for Children and Families and the Sam and Rose Stein Endowed Chair in Child Protection at Rady Children's Hospital-San Diego, delivered the School of Social Work's 29th Annual Edith Harris Endowed Lecture on the topic of trauma-informed systems, which are sensitive to the needs of children experiencing traumatic stress. Child traumatic stress, which occurs when a child or adolescent is exposed to a traumatic event or situation that overwhelms their ability to cope, can cause a range of problems including disturbed sleep, difficulty concentrating, anger, and withdrawal. If untreated, it can result in psychiatric conditions such as posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, anxiety, and a variety of behavioral disorders.

Wilson, who began his social work career as a front line child protection worker in Florida and Tennessee in the 1970s, said the move toward trauma-informed systems began 30 years ago with the realization that the child welfare system, while well-intentioned, involved a segmented, repetitious and often frightening experience that exacerbated children's emotional distress. Children who had experienced trauma were given little voice in the personal items they took with them upon removal from the home, were placed is settings and situations that often triggered memories of their traumatic experience, and were required to recount their experience multiple times to child welfare workers, police, doctors, mental health practitioners, attorneys, and other service providers throughout the system.

"We thought we were rescuing these children, but they didn't feel rescued," Wilson recalled. "We were making it worse."

The value of bringing law enforcement, criminal justice, child protective services, and medical and mental health workers onto one coordinated team was demonstrated by The National Children's Advocacy Center, which was created in 1985 in Huntsville, Ala., and has served as a model for more than 900 Children's Advocacy Centers in the United States and around the world. In 2000, Congress established The National Child Traumatic Stress Network (NCTSN) to pursue systems change by bringing together university-, hospital-, and community-based centers and thousands of national and local partners to offer training, support, and resources to providers who work with children and families exposed to trauma.

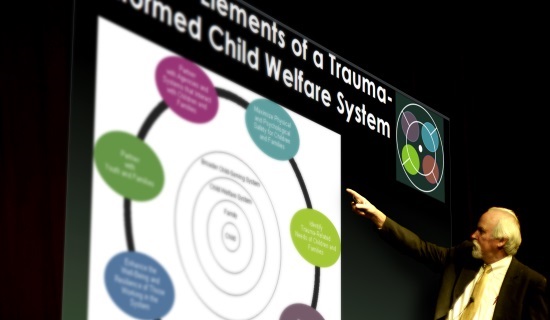

According to Wilson, who co-chairs NCTSN's Child Welfare Committee and is a former NCAC executive director, trauma-informed systems maximize the physical and psychological safety of children and families, identify their needs through screenings and assessments, give children control and choices whenever possible, rely heavily on collaboration and partnerships, and enhance the wellbeing and resilience of children, families, and all of those working in the system. Secondary traumatic stress, which afflicts those helping victims of traumatic stress, creates "second victims" who suffer extreme distress and need organizational support, he said.

Specialists in trauma-informed systems are also less likely to diagnose trauma sufferers with behavioral disorders, Wilson pointed out.

"We have a mental health system that looks for pathology," he said, noting that the most common diagnoses for children in the child welfare system include reactive attachment disorder, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, bipolar disorder, and conduct disorder. However, many of the children with these diagnoses have complex trauma histories, and their diagnoses "generally don't capture the full extent of the developmental impact of trauma."

Early identification of traumatic stress is critical, Wilson said, because it can produce neurobiological effects, psychosocial effects and health-risk behaviors that have serious lifelong consequences. The good news, he said, is that effective treatments exist.

"Tragic events do not need to rob children of their happiness," he said.

For a copy of the 2016 Edith Harris Lecture PowerPoint presentation click here.