William Iverson Jr.: A Century of Driving America Forward

A light in the dark

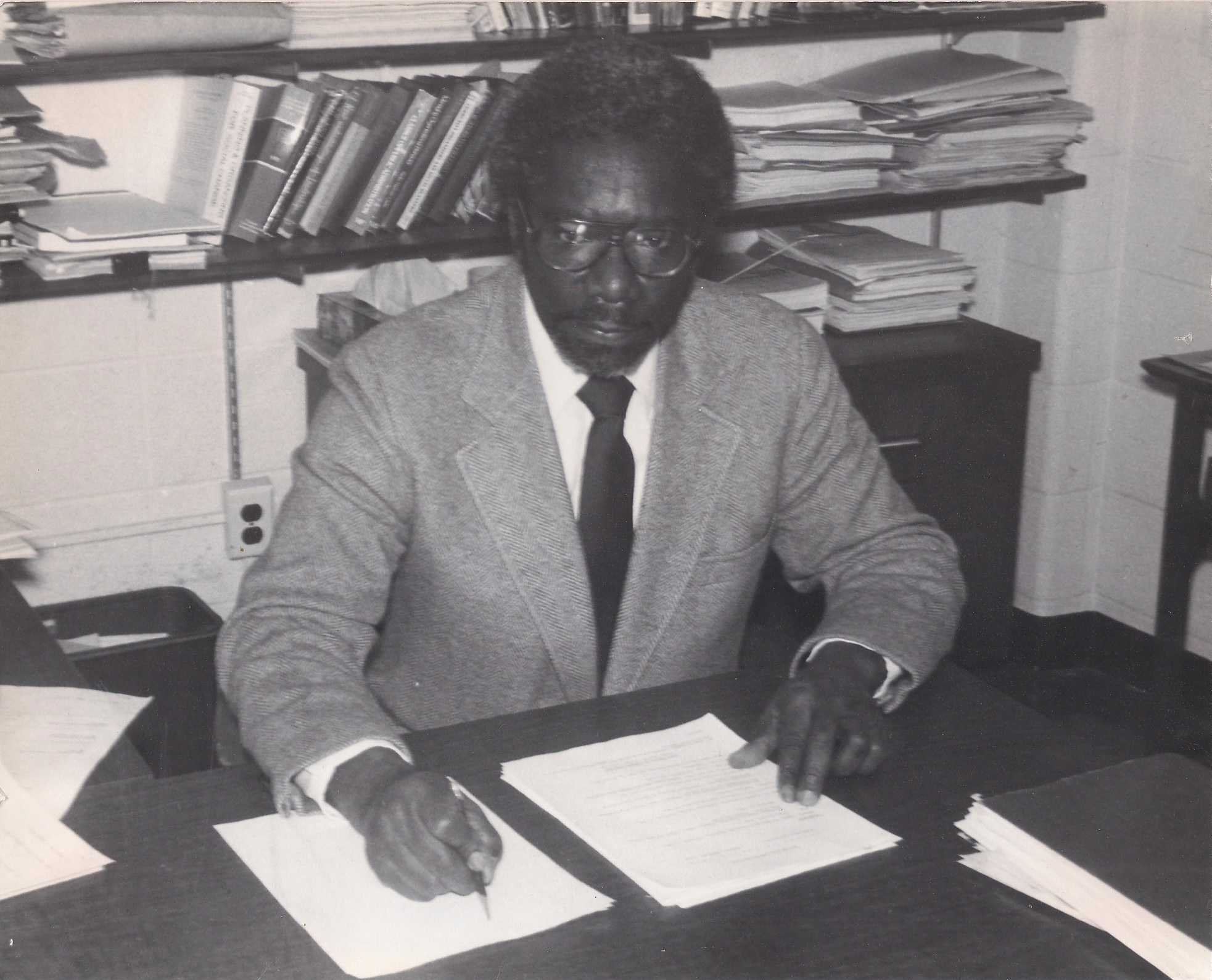

For twenty-two years, the Wayne State University School of Social Work had a hero of World War II and the 1960s civil rights movement working in their midst. As a Part-time Faculty Member, Academic Advisor, and Director of Admissions for the School, William H. Iverson Jr. helped thousands of students along their journey to becoming social workers. Before then, he had already lived a remarkable, if unceremonious life.

In 1944, Iverson spent countless hours driving all night along France's winding debris-laden roads working to support the allied efforts in WWII. Hundreds of trucks like Iverson's hummed along like marching ants as part of one of the most crucial caravans in American history, the Red Ball Express, whose name derived from an old term for mailing something as fast as possible. Railroads in France had been destroyed by heavy bombing and the Red Ball Express was given the enormous responsibility of supplying American forces on the front lines. By the time the Red Ball Express was decommissioned on November 16, it's 6,000 trucks had transported 412,193 tons of supplies to the front and consumed 800,000 gallons of gas. On its most productive single day, 958 vehicles successfully transported 12,342 tons of supplies.

Iverson said he had no idea what to expect from war while crossing the Atlantic, but said he took his risky responsibility in the Red Ball Express with an immense sense of pride. "Sometimes it was overnight, sometimes it was two or three days. We had to get it done. And that could be very dangerous. We couldn't put our headlights on. We had to use little light bulbs that they put in the trucks so we could see each other. And that was the only reason we were able to carry troops around at night," Iverson said. "I think a lot of the missions were at night to avoid detection. Plenty of risk in that driving. We had some pressure to get things done."

Three-quarters of all Red Ball Express soldiers were African American. The Army was segregated and African American troops like Iverson were most often relegated to service units like the Quartermaster Corps. Iverson said that his mission was so critical; he couldn't let segregation get to him.

We trained as segregated troops but for some strange reason, I didn't let too much of it affect me. White troops and Black troops, they didn't mix together, it was kind of a dreadful experience, but I knew I had a responsibility to this country and I went through that fairly well. - William Iverson Jr.

Returning to a nation brimming with racial tension was a struggle. "I did not feel segregation or prejudices there in Europe. I usually felt that in America," noted Iverson. "Serving a country that didn't appreciate me to the same extent as my white counterpart was a hard pill to swallow. When Black American Jessie Owens won an Olympic medal inside Nazi Germany but did not receive an invitation to the White House, it was an example suggesting that an unequal welcome awaited Black veterans back home compared to White veterans."

Amber N. Mitchell '13, the Director of Programming at STEM NOLA, and former Assistant Director of Public Engagement at the National WWII Museum said that the experience of Black WWII veterans is a complicated one.

"The contributions of African American service members during World War II were as immense as any other group during that time. However, much of their contributions, other than a few unique groups and events, go largely unknown by the American public," Mitchell said. "Black troops often were tasked with some of the more menial and dangerous jobs--including that of the Red Ball Express."

Mitchell added, "For many Black service members, the irony of fighting for freedom and democracy abroad while experiencing second-class citizenship in the armed forces and back home was not lost on them. Segregated units were the standard in the military until Executive Order 9981 in 1948. The Double V Campaign, championed by the NAACP, brought attention to that double standard, calling for 'Victory at Abroad, Victory at Home.' Once soldiers returned home, many became active in the Civil Rights Movement, like Medgar Evers and Vernon Damon, calling for the same rights that they had been defending for others overseas".

Helping on the homefront

Though he was in charge of driving supplies, Iverson said he had been trained to do anything to help America win the war. He said the experience led him to believe he could help solve other problems back home.

I was equipped to do almost anything. I was trained to shoot a gun, I was trained to fight hand-to-hand, and trucks were just another assignment. I also had assignments working with people who had real problems, real, real tangible problems. And that's when I moved from truck driving to the management of a social work agency after the Army. My time in the Army sort of put me on the path to wanting to help people with problems. - William H. Iverson Jr.

Iverson was born in Columbus Ohio in 1921, the youngest (and now, only surviving) of nine children. Before the war, he worked in the Civilian Conservation Corps and then as a train porter. After WWII, Iverson received his bachelor's from Capital University, then went on to receive his master's in social work from The University of Illinois in Chicago. In the 50s and 60s, Iverson worked as a social worker with youth in Cleveland and then Chicago, where he was the Executive Director for the Chicago Hyde Park Neighborhood Club. Ultimately, Iverson landed in Detroit where he became an Assistant Professor at the Wayne State School of Social Work from 1969 until retirement in 1991.

I've always wanted to help other people, even when I was a small child. I've always wanted to help people. That's been my logo for a long time - William H. Iverson Jr.

Iverson said social work skills helped him connect with embattled youth in Cleveland in the 1950s. "I mainly worked with what they call street gangs. And these fellows were mean and wild and uncooperative -- they would destroy, in a minute. And as a leader, I had to work with them and sort of calm them down and give them some reality," said Iverson. "So I met with them, I talked with them, and I told them what I would or would not do. And because of that fact, they kind of liked me and had some love for me, they accepted me. And over time that feeling changed and they became better boys"

From Cleveland, Iverson moved to Chicago where he served as Executive Director of the Hyde Park Neighborhood Club. There, Iverson said it was critical to truly, genuinely connect with clients. "I think many of those kids were lonely. They needed somebody to talk to. Probably didn't have a good father or mother. And so I was that person. I cared for them and they cared for me."

In the 1960s, Iverson was a Freedom Rider and marched on the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama. "I was able to get to Selma, Alabama and cross the bridge at that time. It was very important for the country. I was in Chicago and we formed a group that took a bus to Selma," Iverson said. "I think most of us were afraid that we would get killed or shot. And we were very careful about how we went and walked and talked and so forth." Iverson added that even though some were afraid to risk their lives in the civil rights movement, there was no way he was going to sit back on the sidelines. "But I was determined to go because I had a need to go. I wanted to go," Iverson said. "And so I went."

Iverson went on to join the School of Social Work from 1969-1991 and inspired students to empower social change in their communities in various roles including as part-time faculty, advising staff and as the director of Admissions and Student Services. Nowadays, Iverson resides at a retirement village in Grand Rapids, Michigan. Last November, a trumpeting group of Black ROTC officers and city leaders honored Iverson in a private ceremony, thanking him for his life's work as a veteran,

academic, and trailblazer, leading the way and opening doors for future generations. Iverson sat with his son Mark, reading a letter from Michigan Secretary of State Jocelyn Benson celebrating Iverson's contributions to society. Iverson was further celebrated by the Gerald R. Ford Museum Greatest Generation Committee in Grand Rapids as part of their socially-distanced festivities celebrating seventy-five years since the war.

Iverson credits his faith for his longevity and impactful life. He said that for many years he would run 5-10 miles every morning, but now he spends his days watching sports, listening to music, and sometimes singing too.

Iverson, who turns 100 this spring, said he has seen both progress and regression when it comes to racial justice and equality. "I have mixed feelings. I think sometimes we're making advances. And again, when I listen to news from places, I wonder whether we're making advances or not," Iverson said. "I guess statistically, we are making advances, but it's very hard to discern that because of so much mess in the world".

Iverson added that he's thankful for what he learned on the roads of Europe all those years ago.

I'm grateful that I had a chance to go into the Army because it meant I could go to school and learn. That was my mother's wish for years that I would make something of myself. And I think I did. I think I did affect the lives of some people, as I think back now.

This spotlight was written by CLAS Alumni and Donor Relations Officer Steve Zoski.